The story begins in 17th century France.

Lacking the immediacy of modern telecommunications, Louis XIV’s spinners constructed an elaborate media machine that would generate an image of their young monarch as demi-god and disseminate it to the oppressed masses in order to win over public opinion.

An entire art school and spinoff artistic tradition was established specifically to support this very endeavor—to make Louis look good—as well as to help him decorate his new house. And so the revered Académie française came to be, recruiting the most promising artists of its day via an elaborate and well-publicized competition where the contestants were held captive in their studios for 106 days and directed to paint a specific allegorical theme. The grand prize winner of the coveted Prix de Rome was sent (woo-hoo) on an all-expenses paid vacation at the Villa Medici in Florence, where he could churn out Italianate masterpieces to his heart’s content. These, of course, were all shipped back to Versailles to cover its many empty walls.

The Prix de Rome competition would spawn a tradition of grueling, battle-to-the-death contests that continues today and includes most notably the Tour de France race. The mere suggestion of a contest seems to send a frisson of pleasure through many people in that country. But to me the most fascinating element in this story lies in the wacky propaganda machine that was spawned during Louis’ reign. Commisioned paintings of the young king often depicted His Royal Louis-ness surrounded by a writhing community of supporting players—hovering angels, genuflecting villagers, pointing bystanders and bleeting animals—whose sole collective purpose was to make Louis look good.

Now, fast-forward to Thanksgiving Day, 2003, to Bush's surprise visit to the Baghdad airport. Known as the famous

Turkey Shoot, this choreographed photo-op would both spur a tsunami-sized wave of patriotism in the United States and, well, make George look good.

And so he stands, demonstrating protective assurance like a compassionate monarch as he holds the perfect turkey on a platter before grinning soldiers. It has since been reported that the dead bird was in fact a plastic stand-in, no doubt a cruel joke to the participating troops. Whether or not this is true is beside the point, because the entire apparition was strategized like a 17th century painting; its importance didn't lie in the turkey, but rather in the gesture that it represented.

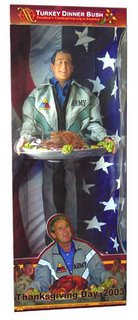

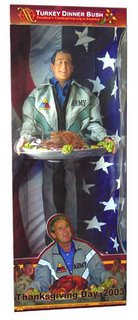

Within 24 hours, George’s public relations people had successfully painted an image that would have taken Louis’ boys at least 24,000 hours to orchestrate. Today you can even buy a

Turkey Dinner Bush talking doll—complete with plastic bird—that utters phrases like: "I was just looking for a warm meal somewhere," and "Thanks for inviting me to dinner... I can't think of a finer group of folks to have Thanksgiving dinner with than you all."

Sadly, the term

Turkey Shoot is also used to describe a decidedly one-sided battle. It’s no accident that the term ‘spinning’, commonly used to describe the creation of media stories, is better suited to yarn. As in lies. As in pulling the wool over…

Ewe get the picture.

[with inspiration from Dr. Amy Schmitter, "Representation and the Body of Power in French Academic Painting," Journal of the History of Ideas 63, no. 3, July 2002, pp. 399-424.]

And so he stands, demonstrating protective assurance like a compassionate monarch as he holds the perfect turkey on a platter before grinning soldiers. It has since been reported that the dead bird was in fact a plastic stand-in, no doubt a cruel joke to the participating troops. Whether or not this is true is beside the point, because the entire apparition was strategized like a 17th century painting; its importance didn't lie in the turkey, but rather in the gesture that it represented.

And so he stands, demonstrating protective assurance like a compassionate monarch as he holds the perfect turkey on a platter before grinning soldiers. It has since been reported that the dead bird was in fact a plastic stand-in, no doubt a cruel joke to the participating troops. Whether or not this is true is beside the point, because the entire apparition was strategized like a 17th century painting; its importance didn't lie in the turkey, but rather in the gesture that it represented.

This nature morte is by the Dutch game painter Jan Weenix, and is currently held in the collection of The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Entitled Still Life with Swan and Game Before a Country Estate, it was painted around 1685. The nature depicted in this painting does look rather dead, don't you think?

This nature morte is by the Dutch game painter Jan Weenix, and is currently held in the collection of The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Entitled Still Life with Swan and Game Before a Country Estate, it was painted around 1685. The nature depicted in this painting does look rather dead, don't you think?